Product successfully added to your shopping cart

There are 0 items in your cart. There is 1 item in your cart.

![Lodovico Ughi: Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia Consacrata al Reggio Serenissimo Domino Veneto Antique Maps, Ughi, Italy, Venezia, Venice, 1729 [1739]: Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia Consacrata al Reggio Serenissimo Domino Veneto](https://www.vintage-maps.com/4290-large_default/ughi-italy-venezia-venice-1729-1739.jpg)

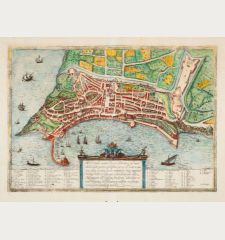

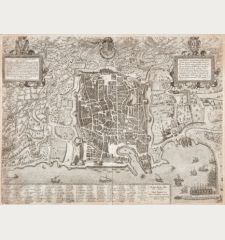

Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia Consacrata al Reggio...

Lodovico UghiReference 12789

Description

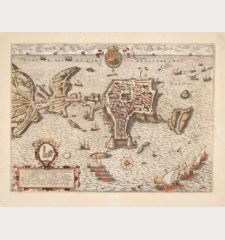

Ughi's Important and Rare Wall Map of Venice.

Lodovico Ughi, the author or dedicator of the map, remains a rather elusive historical figure, with limited information available about his life and background. Some sources have suggested that Ughi hailed from either Bologna or Ferrara, although these details remain unverified. What has endured through history, however, is his enduring legacy as the creator of the 1729 wall map, which stands as an epochal and definitive representation of Venice.

Ughi's map of Venice in one of the largest maps of Venice ever published, and the first map of the city based upon accurate field surveys. Spanning more than 2 meters (nearly 7 feet) in width, the expansive map is adorned with 16 vignettes, engraved by Francesco Zucchi after Luca Carlevarijs (1663-1730). These vignettes flank the map and offer captivating views of the city. The map also features eight columns of text detailing the city's principal sites and structures.

The Importance of the Ughi Map as a Cartographic Document and as a Work of Art

Lodovico Ughi's topographical map of Venice represents a pivotal moment in the history of Venetian cartography. Traditionally, Venetian mapmakers tended to replicate each other's work, resulting in minimal alterations to the city's visual representation over the centuries. However, there were two notable exceptions: Jacopo de Barbari's remarkable bird's-eye view of Venice, printed in 1500, and Ughi's map from 1729. These two maps not only hold the distinction of being the largest printed maps of Venice but also served as enduring models for all subsequent depictions of the city.

De Barbari's bird's-eye view provided a unique perspective, capturing the city from a high oblique angle. This allowed cartographers to convey the vertical dimensions of buildings and architectural features while maintaining a horizontal perspective through the clever use of perspective rather than adhering strictly to true scale. The primary aim was to impress the viewer with its artistic prowess.

As the eighteenth century ushered in advancements in science and technology, urban cartographers adopted more accurate and functional surveying and measuring techniques. By the 1730s, bird's-eye views no longer met the standards of accuracy demanded by urban surveyors. Instead, they turned to the topographical map - a less ornate but more precise ground plan.

The Ughi map marks a significant shift in Venetian cartography as the first and largest topographical map of Venice based on meticulous field surveys rather than the observation and replication of existing maps. It was republished twice more during the century and remained the foundational reference for all subsequent topographical representations of Venice until the Republic's downfall in 1797. Through various copies and adaptations, it continued to dominate Venetian mapmaking well into the nineteenth century.

Iconography and Printed Information on The Ughi Map

The inclusion of images on maps holds profound significance, as it not only conveys geographical information but also provides a visual narrative of a city's grandeur, wealth, and multifaceted greatness, encompassing political, commercial, and military aspects.

During the period when the Ughi map was created, Venice had maintained its independence as a republic for nearly a millennium. Throughout much of this history, Venice stood as a dominant force in the Mediterranean, serving as a critical crossroads between the East and West. It was renowned as the wealthiest and most prosperous commercial center in the civilized world. This historical context, as eloquently put by Jan Morris, reflects Venice's remarkable confidence in its endurance, coupled with its flair for ceremony and effective self-promotion.

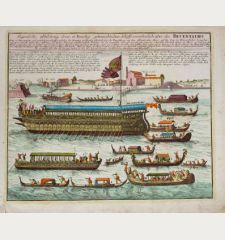

The Ughi map, in essence, serves as an advertisement for the city of Venice, accentuating its beauty, military prowess, and prosperity. Even the title of the map, "Iconografica Reppresentazione della Inclita Citta di Venezia al Reggio Serenissimo Domino Veneto" (Topographical Representation of the Glorious City of Venice Consecrated in the Reign of the Most Serene Veneto Domaine), underscores its promotional intent. Surrounding the map portion, sixteen exquisite views of Venice are featured, compensating for the absence of the renowned landmarks, attractions, and fortification depictions characteristic of bird's-eye view maps. These views collectively convey Venice's allure, affluence, and military strength.

At the bottom left, near the Morosini shield, putti are depicted holding flags, pikes, and staffs, symbolizing triumphant war-related elements. This references Francesco Morosini, the last warrior Doge, who led the Venetians in their battle against the Turks during the War for Candia or Crete. After 465 years of Venetian occupation, Candia was lost to the Turks in 1669. The siege of Candia, lasting twenty-two years, marked a significant event in the history of Venice as it stood alone in defending the city against Turkish incursions into Western Europe.

The top right of the map features an allegorical representation of Venice, symbolically sailing on the sea, pulled by dolphins, sea creatures, and divinities. The presence of the lion of St. Mark at her feet signifies Venice's union with the Queen of the Sea and the wealth derived from maritime endeavors. St. Mark, Venice's patron saint, further underscores this maritime connection.

In the top left corner, a wind rose is depicted, with each wind direction personified by the head of a putti. The eight major compass points hold particular importance for a city reliant on seafaring trade.

Within the cartouche at the bottom right, there is a dedication by Lodovico Ughi to Alvise Mocenigo, the Doge in 1729. Ughi extols Venice as a "glorious city," blessed by the Virgin, a divine entity, the Queen of the Adriatic, globally recognized for its justice, feared by its adversaries, and defended by its dedicated sons who have sacrificed their lives. This dedication captures the deep reverence and loyalty to Venice during that era.

Notably, due to the large scale of the map, place names are directly incorporated onto the map itself, eliminating the need for reference letters or numbers correlating to a separate text. To differentiate urban elements, streets are depicted with parallel lines, religious buildings feature closer parallel lines and letters, and the rios and canals are represented by wavy lines. Civic buildings are left in white, ensuring clarity and readability.

The Work of Art

The introduction of the printing press marked a significant development in the field of cartography, and the Venetians were quick to harness this technology for map production. Venice, being a bustling mercantile hub, received a steady stream of cartographic information from various corners of the world. The maps they produced served not only the needs of Venetian outposts but also catered to the demands of travelers, scholars, and individuals in positions of governance and military authority. By the eighteenth century, Venice had cultivated the ideal conditions for a flourishing printmaking market. Skilled engravers and book illustrators were highly active, generating a prolific output of prints. Prints offered the advantage of being easily transportable, manageable, and exportable, making them a sought-after commodity.

The printed Ughi map held profound importance within eighteenth-century Venetian culture. The publishers, engravers, and artists involved in its creation represented some of the most talented and productive figures of their era.

The initial publisher of the map, Giuseppe Baroni, was part of a group of six Venetian printmakers and merchants who established a guild of engravers called L'Arte degli Incisori in 1718. This guild aimed to regulate the quality of copper engraving as an art form and sought exclusive rights to its production. Baroni's workshop, or bottega, was situated in Campo S. Zulian, near Piazza S. Marco, where a significant concentration of printers operated.

While not definitive, stylistic evidence suggests that Francesco Zucchi may have been the engraver responsible for the sixteen views of Venice flanking the Ughi map. Zucchi, a member of Baroni's guild, was a prolific book illustrator. The refined prints of these views were directly adapted from Luca Carlevarij's renowned work Fabriche e Vedute di Venetia, published in 1703. Carlevarij was one of Venice's celebrated vedutisti or view painters.

Recent studies have yielded a significant discovery related to the Ughi map. An exquisite drawing titled Venezia Trionfonte, attributed to the esteemed Venetian painter Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734), has come to light. This drawing can now be firmly established as the preparatory artwork for the allegorical figures positioned in the upper right portion of the Ughi map. The drawing is housed within album #56, part of the library collection belonging to Anton Maria Zanetti, which is preserved in the Academia Gallery in Venice. Anton Maria Zanetti was not only a friend of Sebastiano Ricci but also a patron of both Sebastiano and Marco Ricci. This newly identified drawing provides valuable insights into the artistic process and collaborative efforts that contributed to the creation of the Ughi map. Sebastiano Ricci's Venezia Trionfonte serves as a critical link between the world of painting and cartography, shedding light on the interconnectedness of artistic disciplines during this period and enhancing our understanding of the map's iconography and cultural significance.

Upon Baroni's passing, records indicate that the copper plates used for the Ughi map were among the assets listed in his workshop's inventory. Lodovico Furlanetto, the second publisher of the map, acquired these plates when he purchased the entire inventory from Baroni's estate. Furlanetto continued to print the map for at least six decades, with his own name replacing Baroni's in the lower right corner.

Rarity

The Ughi map was intended to be hung on a wall mounted on linen. A map hanging on a wall will not survive this condition for long unless it is stored and handled in the gentlest way possible. The fastenings tear, the glue between the paper and the support fails, and the materials become brittle and damaged by the environment, insects, handling, and rolled storage. Thus, only a few copies of this monumental wall map of Venice have survived.

We have been able to trace copies of the large Ughi Venice map in the following libraries and public collections: Bibliothèque Nationale de France; Houghton Library, Harvard; Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (without borders); Zentralbibliothek Zurich (without borders); Leiden University Library; Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Dresden; Museo Correr, Venice; The Royal Collection, London; Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence; Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice. At Sotheby's in London, one sold for GBP 16,250 in 2009 (Sale L09774) and another one sold for GBP 12,500 in 2017 (Sale L17401). At Christies in London (sale 7164) in 2005 for GBP 8,500 without side banners und another example at Christies (1998 sale 6111, also without the 16 views) sold at GBP 12,075.

Details

| Cartographer | Lodovico Ughi |

| Title | Iconografica Rappresentatione della Inclita Città di Venezia Consacrata al Reggio Serenissimo Domino Veneto |

| Publisher, Year | Lodovico Furlanetto, Venice, 1729 [1739] |

| Plate Size | 145.7 x 201.6 cm (57.4 x 79.4 inches) |

| Sheet Size | 154.5 x 206.5 cm (60.8 x 81.3 inches) |

| Reference | Susan Filter, Historic Intent: Lodovico Ughi's Topographical Map of Venice; A Large Wall Map as an Historic Document, a Work of Art, and a Material Artifact, The Book and Paper Group Annual 13 (1994); Schultz, J.: The Printed Plans and Panoramic Views of Venice (1486-1797), No. 117; |

Condition

Cartographer

Images to Download

If you like to download the image of this map with a resolution of 1200 pixels, please follow the link below.

You can use this image for publication on your personal or commercial websites for free if you set a link to this website. If you need photographs with a higher resolution, please contact us.

Italy - Ughi, Lodovico - Iconografica Rappresentatione della...

![[Sardigna, Sardinia, Sardegna] [Sardigna, Sardinia, Sardegna]](https://www.vintage-maps.com/2947-home_default/bordone-italy-sardinia-sardegna-1528-1565.jpg)